Le Corbusier (1885-1965), the Swiss born architect, is considered both the High Priest and enfant terrible of twentieth century modernist architecture and town planning. He helped to define and clarify an approach to urban design and planning that provided a vision of the future city. Many of the criticisms of Le Corbusier’s vision stem from often-botched attempts to realise his ideas in post war social housing but more fundamental criticisms relate to his methods and failure to plan on a human scale.

Le Corbusier emerged from the Great War as a leading and radical proponent of modernism. His radical ideas originated from his desire to improve living conditions for the urban poor and his own development drew upon the contemporary zeitgeist of cubism (which he rejected in favour of ‘purism’), futurism and modernist minimalism. Like his contemporaries Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Eileen Gray, et al, he sought to simplify and rationalise modern design and building methods by the use of straight lines and the modern materials of steel, concrete and glass.

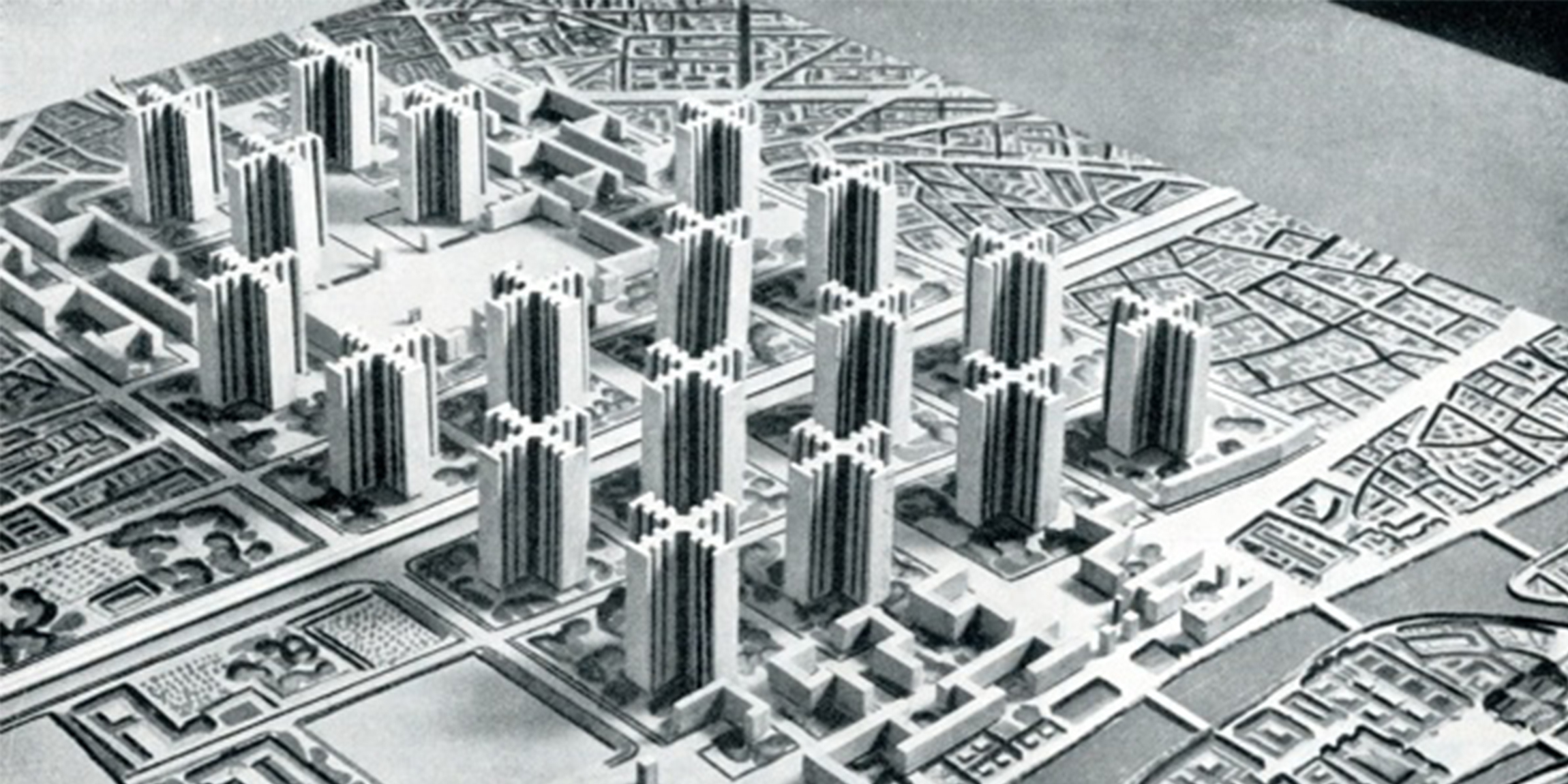

Le Corbusier thus emerged as a leading advocate of the new discipline of town planning in the 1920s. He entered into various architectural competitions and through his writings propagated novel solutions to the problems of urban poverty, overcrowding and congestion and gridlock. His approach sought to bring a new rationalist approach to town planning and urban housing. His cities were to be laid out in a strict symmetrical grid pattern, with neatly spaced rows of identical skyscrapers – what he termed ‘Cities in the Sky’. Le Corbusier plans were for cities of steel and concrete dominated by wide highways and large skyscrapers organised in regimented, park-like settings. It was a vision of underpasses, skyscrapers, free-flowing traffic, steel, concrete and glass.

Le Corbusier’s own attitude to domestic architecture is captured in his description of houses as ‘machines for living’. However, the minimalism of his approach should not be confused with a lack of attention to detail or design. Indeed, like his contemporaries, Le Corbusier lavished considerable time and detail on the interiors and furnishings of his buildings. His machines for living needed to be furnished by suitable Machine Age furniture, such as his LC2 chair, the ‘relaxing machine’ LC4 Chaise Longue, and the LC10 dining table. These are still heralded as classic examples of contemporary designer furniture.

During the inter-war period, despite his growing international reputation, Le Corbusier had limited success in actually realising his plans. He sought to influence planning in France, the Soviet Union and elsewhere in Europe, and politically became a fellow traveller of the far-right in 1930s France, and accepted a role in the wartime Vichy administration.

After the war Le Corbusier was offered an opportunity to implement some of his radical town planning ideals by the Gaullist government in France, and Unite d’Habitation is his most notable example. Le Corbusier was also remarkably influential in the postwar town planning movement elsewhere Europe and beyond.

One example of his influence can be found in Britain. Here, post war housing policies began with high ideals of providing affordable but desirable public housing that would appeal to middle class as well as working class citizens. With an eye to the earlier successes of the Garden City movement, the initial focus was on building high quality, low-density low-rise council housing.

However, under pressure to reduce costs from 1950, successive housing ministers sought cheaper building methods. Le Corbusier’s ideal of Cities in the Sky thus found increasing favour with post war British town planners as an ideal solution to postwar slum clearance and town planning. Tower blocks offered a high-density solution that was more affordable than the low- rise housing favoured by the Garden Cities movement and the Attlee government.

Unfortunately, if predictably, the resulting high-rise estates were not a success. To start, England (unlike Scotland) does not have a tradition of living in tenements or flats. The English urban landscape is defined by low-rise terrace and semi-detached housing while the tower block had no relationship to English or Welsh traditions.

To compound this issue, often the tower blocks were constructed without reference to Le Corbusier’s far more radical plans for urban renewal. Also, settled slum communities were broken up and the community ties irrevocably ruptured. Residents often complained of isolation and for some the tower block became synonymous with imprisonment. Public confidence was also undermined by disasters such as Rowan Point in 1968, which pointed to a problem of poor design and build quality. Finally, very few of the town planners and architects built tower blocks that they themselves would want to live in – they built sub standard high-rise housing for the urban poor.

Often poorly constructed, these high-rise estates became synonymous with urban blight and deprivation and, plagued by social and economic problems, were colloquially known as ‘sink estates’ from the late 1980s. Le Corbusier’s dream of Cities in the Sky is popularly seen to have failed in England to such an extent that many public housing tower blocks are demolished long before their anticipated end of life is reached.

Despite his enormous influence on postwar town planning and architecture, Le Corbusier’s reputation today is tarnished both by his own political trajectory and by the perceived failings of his approach to contemporary urban living. His emphasis on rationalism and efficiency resulted in plans that put the car before the citizen. His conception of the house as a ‘machine for living’ relegated people’s emotional relationship with their home. His championing of tower blocks of steel and concrete is criticised for producing a brutalising architecture that sacrificed concerns of human scale and feelings on the altar of rationalism and efficiency. Given his contemporary reputation, it’s unlikely that the British government’s plans for new garden cities will draw too closely on Le Corbusier’s ideals.